Climate, Fisheries, and Food Cultures: How are fisheries changing as the climate warms? And how do food cultures respond to these changes?

It’s all over the news: the planet is warming. It can be easy to think about climate change as something that is happening far away, limited to melting glaciers and summer droughts. However, as more research is done about global warming, it is becoming increasingly clear that the warming planet is beginning to impact people all over the world.

In this series, we’ll be talking about how global warming is impacting fisheries and food cultures, specifically in the Mid-Atlantic region.

To begin, we want to share some research from Fishadelphia’s own Dr. Talia Young. Talia, along with Valerie Erwin, Ebony Graham, and Gabriel Cumming, published a paper in 2024 about the impacts of globalization and climate change on the food cultures of Black Americans in the Mid-Atlantic. To study this, they interviewed nineteen Black Philadelphians who had roots in the South, asking about the ways that they consumed seafood.

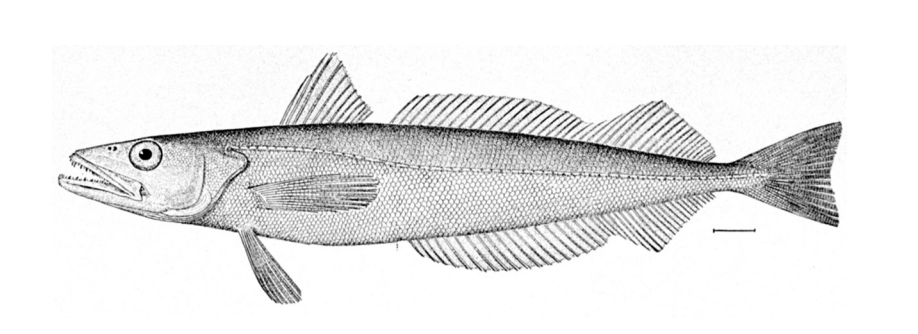

Growing up, these Philadelphians would usually eat fish during Friday family dinners. The fish, prepared by family and other community members, was commonly whiting, porgy, or other regional species. In the present day, though, their fish consumption was more varied – there was no common day on which they would eat seafood, and regional species made up less than half of the species they ate. There were other changes too; while frying was the most common preparation method when these Philadelphians were growing up, in the present day, baking was just as common as frying. These Philadelphians also shifted in their seafood purchasing locations – grocery stores were the most common purchasing site in the present day, as opposed to the fish markets of the Philadelphians’ youth.

So, how does this relate to climate change? Whiting – the species most often mentioned by the interviewed Philadelphians – is no longer found in Mid-Atlantic waters. The species has migrated north, in search of cooler waters, making their own sort of “Great Migration”. While the prevalence of whiting has decreased, though, the globalization and commercialization of the seafood market has allowed the seafood species selection to explode. This explosion of species selection can mask the impacts of global warming on regional seafood markets, while simultaneously contributing to the mass combustion of fossil fuels through the shipment of seafood across the globe.

Despite these changes, though, Black Americans in Philadelphia have always had strong connections to regional seafood markets, and their foodways are resilient. As written in Talia’s paper, “For Black Philadelphians, preparing fish is not just about nourishment; it is about reinforcing the generational bonds that knit families and communities together. As communities worldwide face unprecedented change, this sustaining desire to come together around food will be essential to cultural and ecological continuity.”

Regional seafood markets will change as the planet warms. However, by being resilient and building community, we can hold on to the cultural and ecological continuity that has sustained us for generations.